Indonesian cultural journals have played a great role in the production of modern Indonesian literature and in the Indonesian publishing scene in general (Kratz 1994). As many authors did not have the financial means to have their works printed in book form, authors of short stories and poetry had only the choice to get published in journals and newspapers. Ulrich Kratz has demonstrated the great importance of journals for the production of modern Indonesian literature in his monumental bibliography of nearly 900 pages. It is not surprising therefore that those cultural journals of nation-wide importance like Horison, Zenith, Mimbar Indonesia, Basis, Pujangga Baru or Medan Sastera, to mention only a few, are comparatively well available in European libraries and collections. Local periodicals like Pawon (Surakarta), Puisi (Magelang), Catatan Kebudayaan (Denpasar) or Genta Budaya (Padang) which often appeared for only a few years are far less represented. Cultural journals for children and young readers are nearly totally absent in Western collections.

The Library of Southeast Asian Studies at Goethe Universität Frankfurt am Main acquired in 2011 the collection of books of Prof. Ulrich Kratz, formerly professor at the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London. Ulrich Kratz was a regular visitor of the Malay world since the early 1970s and acquired many rare titles published locally. His main research interests were literature and culture, so his library consisted of more than 9,000 titles from Indonesia, Malaysia, Brunei Darussalam and Singapore, mainly in Indonesian/Malay.

Among the many periodicals in the collection of Ulrich Kratz is an incomplete set of the first two volumes of the Indonesian childrens’ journal Tjenderawasih: Madjalah Bulanan Anak-Anak (‘Bird of Paradise: Monthly Magazine for Children’), which so far is not listed in the World Cat and thus being unique.

Illustration 1: Front cover of the first volume that was released in September 1951

Its first volume was released in September 1951, and the last available issue is volume 2, Number 7, published in June 1953 (illustration 2). All issues were published by Ganaco, a well-known publishing house in Bandung from the 1950s to the late 1970s. It is not known when the journal ceased its publication.

Illustration 2: Front cover of volume 2 number 1 of Tjenderawasih

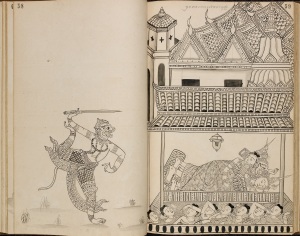

The journal describes itself on its back page as a “magazine for our children based on education” (madjalah anak² kita jang berazaskan pendidikan) managed by “experts of education” (ahli² pendidik). Therefore its contents were considered suitable for all classes in Indonesian elementary schools and were adapted to their courses of instruction. What, then, are the contents of Tjenderawasih? We find in it short stories und poetry, inspirational songs, games and riddles, cartoons and illustrations, Hari Raya wishes, reports (e.g. on a soap box derby in Jakarta in 1952) or educational texts on geography (e.g. the Great Chinese Wall, see illustration 3 below) or history (e.g. on Robert Baden Powell and the Boy Scouts movement).

Illustration 3: Tjenderawasih volume 2, number 2, p. 9: Tembok Tiongkok (‘The Great Chinese Wall’)

Short stories, reports, songs and cartoons reflect very well the nationalist spirit of Indonesia in the early 1950s when the country still suffered from the traumata of the Japanese occupation in the Second World War and four years of the Indonesian Revolution 1945-1949. The hilarious cartoon shown below is a good example: Indonesian national schools had to teach the new national language Bahasa Indonesia to native speakers of Javanese, Sundanese, Batak and hundreds of other languages.

Illustration 4: Tjenderawasih volume 2, number 7, p. 23: Politik – Politur

The new language, still being unfamiliar to many, led to funny creations when it came to the formation of new words. Several short stories were written for entertaining its young readership by presenting exotic and adventurous tales like the story of the American Indian girl Mega Putih and the red bear (illustration 5) or the Eskimo boy Ikwa (illustration 6).

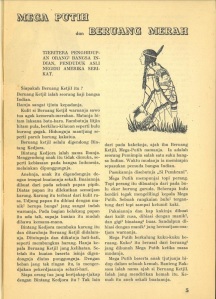

Illustration 5: Tjenderawasi volume 2, number 7: p. 5: Mega Putih dan beruang merah (‘Mega Putih and the red bear’)

Illustration 6: Tjenderawasi volume 2, number 2: p. 13: Ikwa Anak Eskimo (‘Ikwa, the Eskimo boy’)

Only occasionally the articles were signed with an author’s name or an indication of the author, e.g. like “Ibu Tjenderawasih”, most likely the editor S. Rukiah herself. The rest remained anonymous.

The editorial staff of Tjenderawasih consisted of several members, by far the most well-known was S. Rukiah (1927-1996). She was one of the most prolific female authors of Indonesian prose literature of the 1950s, her most well-known novel Kedjatuhan dan hati (‘The fall and the heart’) received much acclaimed critics (Rukiah 1950). In 1951 she moved to Bandung to become editor of Tjenderawasih (Rukiah 2011), although the journal’s editiorials were listed only beginning with volume 2, number 2 in December 1952 mentioning her as editor. Later she became member of the communist influenced cultural organization LEKRA and stopped writing after the mass killings of 1965.

As “pedagocial adviser” (penasehat paedagogi) served Sikun Pribadi, who wrote his PhD at Ohio State University in the United States in 1960 and later became professor of educational science at the Universitas Pendidikan Indonesia in Bandung. A permanent member of the editorial staff was Daeng Sutigna (1908-1984), a well-known performer and teacher of Indonesian Angklung music. Sutigna ran courses on Angklung for the Indonesian Ministry of Education and Culture from 1950 onwards. Further permament members were: 1. A. H. Harahap, author of several reading books for elementary schools together with Oejeng Soewargana, the publisher of Ganaco. Furthermore Harahap wrote a few general introductions on Indonesian geography, e.g. on the island of Madura (Safiudin & Harahap 1956). Haharap was active as author until well into the 1970s, nearly all his works were published by Ganaco; 2. Karnedi, an artist who founded in 1948 the art studio Jiwa Mukti with the well-known painter Barli Sasmitawinata (1921-2007) and Sartono (Mulyadi 2008: 279); 3. E. S. Muljokusumo, a civil servant in the Indonesian Ministry of the Seas and Fishing, who wrote several articles on natural phenomena like the sun, stars, the Indonesian seas and the like; 4. Sudigdo, maybe identical with Muljokusumo; 5. Ibu Suparti, and finally 6. Nn. Rukmini Sudirdjo. On these last three persons no further information was available.

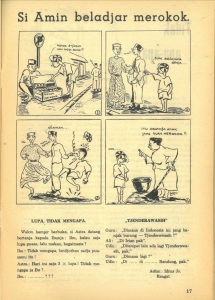

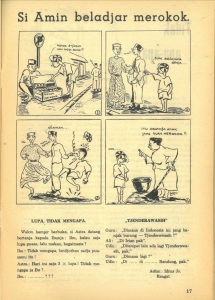

Cartoons were included in the journal on an unregular basis. The magazine was printed partly in colour, but photos and many of the cartoons appeared in black and white. The cartoons were signed with acronyms like “Tosa” for the Si Amin-series (see e.g illustration 7) or “Dana” (Illustration 4). No further information on these cartoonists could be obtained so far. All their cartoons – as well as many other contents in the magazine – show a certain moral or ethics, in particular to strengthen the national spirit among its young readers.

Illustration 7: Tjenderawasi volume 1, number 8, p. 17: Si Amin beladjar merokok (‘Amin learns to smoke’)

A few lines from the anonymous poem Madju dja….lan (‘Way of progress’, volume 1, number 10, 1952, p.3) will illustrate this:

Drap, drap, drap !

Terdengar kaki menderap.

Itulah barisan Sekolah Rakjat

Harapan bangsa, penuh semangat

Beladjar disekolah sungguh-sungguh.

Bekerdja dirumah sungguh-sungguh.

Berbaris dilapangan madju dja…lan !

Itulah anak kemerdekaan …

Drap, drap, drap !

Rhythmic steps can be heard

These are the lines of the People’s School

Hope of the nation, full of spirit.

[They] learn hard in the school.

[They] work hard at home.

[They] line on the square for the way of progress!

These are the children of independence…

Further examples are e.g. a photo series on the celebrations of the national Kartini Day on 21 April 1952 or a report on General Abdul Haris Nasution, the hero of the revolution and one out of only three of Indonesia’s five star generals.

The magazine was published by the Bandung-based publishing house Ganaco, which was active from 1950 onwards until the death of the publisher in 1979. In the 1950s they also had branches in Jakarta and Amsterdam. Its publisher was Oejeng Soewargana (1917-1979; other spellings of his name are Uyeng Suwargana, Oejeng S. Gana, Ujeng S. Wargana or Ujeng Suwargana), a quite well-known figure in the field of education and prolific author of school books and reading books, often co-authored with A. H. Harahap or Amin Singgih (Ensiklopedia 2004, Jilid 15: 170). It is quite interesting to note that Soewargana kept close relations to several high-ranking members of the Indonesian armed forces such as Abdul Haris Nasution and wrote several books on the incidents of 1965, rather from the Orde Baru perspective (Harry Poeze, personal communication), while S. Rukiah as editor of Tjenderawasih was standing on the leftist side.

Ganaco also published in other languages than Indonesian. In the 1950s they produced an English-language magazine Window on the World (see the advertisement in Safiudin & Harahap 1955). In the same period many titles of modern Sundanese literature and on Sundanese language learning came out, but introductory books on member states of the non-aligned movement (e.g. Burma or Saudi-Arabia) were also published.

Tjenderawasih contains no commercial advertisements except those from the publishing house Ganaco itself, although they announced prices for them. Prices ran from 500,- Rupiah (c. 43,- US$) per page, 275,- Rupiah (c. 24 US$) for a half page to 150,- Rupiah (c. 13,- US $) for a quarter page. A yearly subscription of the journal costed 22,50 Rupiah (5,90 US$ in 1951, 1,97 US$ in 1953). Due to its contents and the relatively high subscription rates for Indonesia in the early 1950s the circulation of the magazine was probably limited to young middle and upper class readers of the major urban centres of Java like Jakarta, Bandung, Semarang, Surabaya or Yogyakarta.

References:

Ensiklopedi (2004): Ensiklopedi nasional Indonesia. Jakarta: PT. Delta Pamungkas.

Kratz, Ulrich (1988): A bibliography of Indonesian literature in journals – Bibliografi karya sastra Indonesia dalam majalah. Yogyakarta: Gadjah Mada University Press.

Kratz, Ulrich (1994): La place des revues dans la production littéraire. In: Henri Chambert-Loir (ed.), La littérature indonésienne: une introduction [Cahier d’Archipel 22], pp. 151-158. Paris: Association Archipel.

Mulyadi, Efix [ed.] (2008): The journey of Indonesian painting: the Bentara Budaya Collection. Jakarta: KPG.

Rukiah, S. (1950): Kedjatuhan dan hati. Djakarta: Pudjangga Baru, Special Issue Nov.-Dec. 1950.

Rukiah, S. (2011): The fall and the heart. Jakarta: Lontar Foundation.

Safiudin & Harahap, A. H. (1955): Madura: pulau kerapan [Seri kenallah tanah airmu]. Bandung: Ganaco.

https://id.wikipedia.org/wiki/Daeng_Soetigna [accessed 30 September 2017].

Article by Holger Warnk (Library of Southeast Asian Studies, Goethe Universität Frankfurt am Main)

Recent Comments