Originally composed in India in Sanskrit over two and half thousand years ago by Valmiki, the Ramayana is also one of the most popular masterworks throughout Southeast Asia. This is reflected not only in the literary traditions, but also in the performing and fine arts, as well as in architecture and modern design. The epic tells the story of Rama, his brother Lakshmana and Rama’s wife Sita, who was kidnapped by the demon king Ravana. The main part of the epic is about the fight between Ravana and Rama, who wants to get his wife back. In this battle, Rama is supported by his brother and a monkey chief, Hanuman, with his armies.

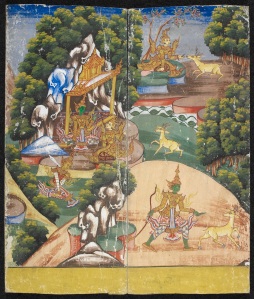

Hanuman facing Ravana asleep in his palace after having abducted Sita. From a 19th century album of drawings by an anonymous Thai artist. British Library, Or.14859, pp. 58-59

Knowledge of the Ramayana in Southeast Asia can be traced back to the 5th century in stone inscriptions from Funan, the first Hindu kingdom in mainland Southeast Asia. An outstanding series of reliefs of the Battle of Lanka from the 12th century still exists at Angkor Wat in Cambodia, and Ramayana sculptures from the same period can be found at Pagan in Myanmar. Thailand’s old capital Ayutthya founded in 1347 is said to have been modelled on Ayodhya, Rama’s birthplace and setting of the Ramayana. New versions of the epic were written in poetry and prose and as dramas in Burmese, Thai, Khmer, Lao, Malay, Javanese and Balinese, and the story continues to be told in dance-dramas, music, puppet and shadow theatre throughout Southeast Asia. Most of these versions change parts of the story significantly to reflect the different natural environments, customs and cultures.

Serat Rama Keling, a modern Javanese version of the Ramayana, illuminated manuscript dated 1814. British Library, Add.12284, ff.1v-2r

When mainland Southeast Asian societies embraced Theravada Buddhism, Rama began to be regarded as a Bodhisatta, or Buddha-to-be, in a former life. In this context, the early episodes of the story were emphasized, symbolising Rama’s Buddhist virtues of filial obedience and willing renunciation. Throughout the region, Hanuman enjoys a greatly expanded role; he becomes the king of the monkeys and the most popular character in the story, and is a reflection of all the freer aspects of life. In a series of articles on the British Library’s Asian and African Studies blog, curators Annabel Gallop, San San May and Jana Igunma explore how the Ramayana epic has been rewritten and reimagined in the different parts of Southeast Asia.

To read the articles, go directly to the Asian and African Studies blog.

Recent Comments