By Holger Warnk (Johann Wolfgang Goethe-University, Frankfurt)

In 2018 the Library of Southeast Asian Studies at Johann Wolfgang Goethe-University acquired the library of Prof. Wilfried Lulei, former Professor of Vietnamese Studies at Humboldt University in Berlin.[1] Among the more than 1,500 books, journals, maps and other materials was a small book by Georges Norès published in 1930, entitled Itinéraires automobiles en Indochine. This booklet is the third and final volume of a travel guide, being one of the first to introduce tourists to the possibilities of travelling in French Indochina by car.

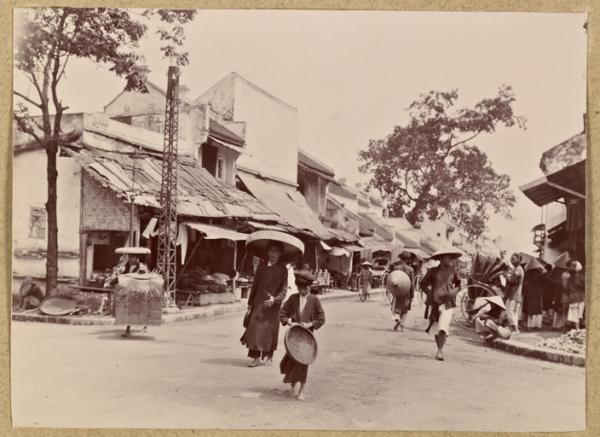

The travelling of Westerners to Southeast Asia has had a long tradition. They came to the region as traders, merchants, colonial administrators, missionaries, military commanders or soldiers, among others, and since the late 19th century more and more also as travellers. Those who were able to visit with no other intention than being tourists were mostly well-off Europeans and Americans such as the British ‘Bengal civilian’ Charles Walter Kinloch (1853) or the well-known German authors Hermann Hesse in 1907 or Max Dauthendey in 1905 and again in 1914 (Hesse 1980; Dauthendey 1924). With the establishment of the European colonies in Southeast Asia, after 1900 the growing tourism became an increasingly important factor of economic progress, including in Indochina where the first local tourist offices were set up on initiative of individuals and hotel owners in 1913 and 1916 (Demay 2014: 76).

While the first touristic activities were directed chiefly to Europeans who were already living in the colony for a while, the extension to those arriving from overseas became more and more lucrative after World War I. Subsequently, the necessary tourism infrastructure was expanded in French Indochina as well as in other parts of Southeast Asia, in particular on the island of Bali. The enlargement of ports, the construction and improvement of roads including bridges and ferries, the extension of the railway system and the introduction of bus services, the identification and opening up of antique, picturesque or “authentic” tourist sites, the establishment of suitable accommodation in the major towns and cities and at scenic spots both at the coast and at hill stations went hand in hand with the introduction of tourist information centres alongside the printing of guide books, brochures and maps, the availability of a good medical infrastructure, and all these measures were further enhanced after the 1920s in Indochina (Bui 2021: 43).

Besides seaside resorts and spas especially hill stations turned out to become popular destinations for tourists due to their comfortable climate and the picturesque landscapes they were located in. Such hill stations were not only typical for the French colonies in Southest Asia: in Ceylon (Nuwara Eliya) and British Malaya (Cameron Highlands) such stations were also set up for relaxation and physical recovery, as well as in the Netherlands East Indies (e.g. around Bandung or Malang) and in the Philippines (Baguio).[2] In French Indochina the hill stations and roads to reach them were developed in close relation, directly or indirectly, with military needs: they were introduced as camps and garrisons for establishing the colonial administration, roads and paths for transportation of troops and supply, and later as sanatoriums for military personnel (Demay 2014: 50; Bui 2021: 47). During World War I began the “demedicalization” (Demay 2014: 78) of the hill stations, resulting in their transformation into tourist accommodation where the former medical equipment became less important. As the presence of automobiles increased after the War, it was only a matter of time that these places received the proper infrastructure so they could be reached easily by car. The tourist guides of Georges Norès are obvious proof of this transformation.

Georges Lucien Constantin Norès (1869–1947) was born in Besanҫon and served in the French Navy from 1889 to 1899.[3] In 1900 he became Inspecteur de 3ème classe des colonies and subsequently made a successful career as colonial administrator in French Indochina. Already in 1902 he was promoted to Inspecteur de 2ème classe des colonies and again in 1905 to Inspecteur de 1ère classe des colonies. In 1912 he was made officer of the French Legion of Honour and became commander of the Legion of Honour in 1922. During his military career Norès served in Madagascar 1895–1896, and during World War I at the Western Front in 1915 – 1916. He became Directeur du Contrôle financier de l‘Indochine in 1922, and towards the end of his service in 1930 Inspecteur général de 1ère classe des colonies. Norès was then posted to Hanoi in Tonkin. With an experience of many years in French Indochina Norès was an expert connoisseur of Laos, Cambodia and in particular Vietnam which enabled him to gather the necessary information for his guide books.

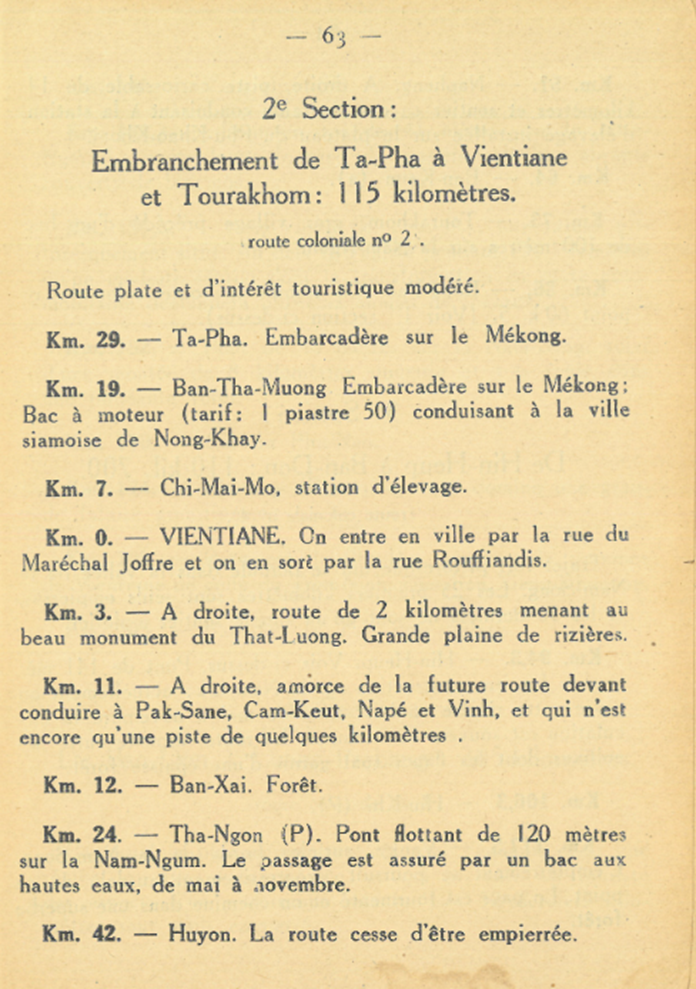

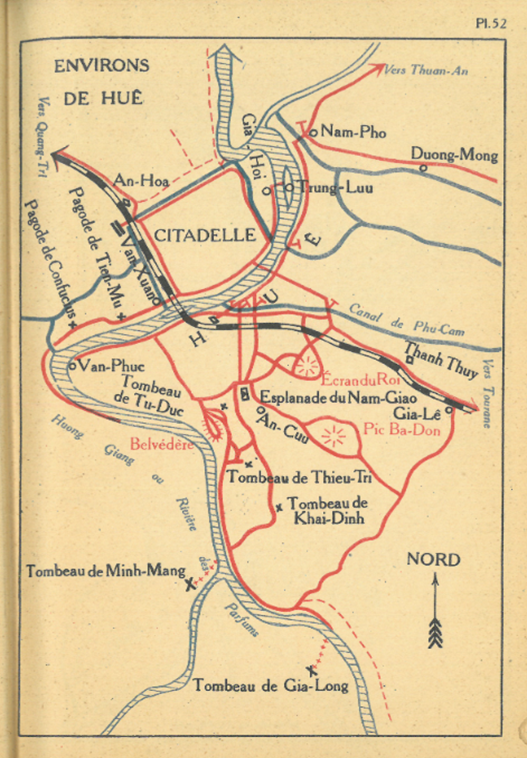

Each of the three volumes consists of about 100 pages plus a considerable number of maps of the suggested automobile tours. As Norès explained in the introduction, his guide was solely tailored to the specific needs of its users (Ponsavady 2018: 104). Besides some short general information on land, people and administration of Annam and Laos he introduces 10 tours suited for travel by car, covering a distance of 70 to 200 kilometers each. After 1900 the French colonial government greatly expanded the infrastructure in Indochina including the planned construction of a north-south highway from Hanoi to Saigon – which, however, was finished only in the late 1930s. But already in the 1920s the ancient Cambodian ruines of Angkor could be reached from Saigon within 18 hours (Bui 2021: 80). Norès gives the necessary information in a most condensed format. Each suggested automobile tour is described with information on locations of sights and what can be seen whilst traveling by car (see illustration 2): besides short descriptions of sidetrips to picturesque spots Norès also refers to matters of everyday significance like gas stations, mechanics, hospitals, telephone and telegraph offices or lodging. The written text is accompanied by several maps which also show the topographical profile of the roads, which is highly important considering the standards of automobile technology in the late 1920s (see illustration 3). Furthermore, they indicate the location of towns and villages, picturesque landscapes, temples and archaeological sites, but also ferries, railway crossings and stations, waterways or mountain passes. Supplementary maps of the most noteworthy cities and towns (see illustration 4) and an alphabetical index of the featured sites for practical use conclude each of his booklets.

The role of the École Franҫaise d’Extrême-Orient as a colonial institution in the promotion of tourism should not be underestimated.[4] The access and development of archeological sites and places of antiquity for tourists and other visitors had already been in the focus of EFEO since the end of World War I. The ruins of Angkor, Cham temples in Vietnam and other archaeological sites were identified by EFEO in the order of their potential as tourist spots, and reported to the French tourist offices in Indochina (Bui 2021: 45; Demay 2014: 106). Consequently, Norès‘ booklets were published by EFEO which secured an excellent print quality for this purpose, a reasonably good binding of the booklets, and a great circulation within and outside the colony.[5]

“Tourism was employed as an effective tool to promote the positive image of the colony”, Bui Thi He stated correctly in her recent MA thesis (2021: 48). These early 1930s automobile itineraries are a vivid proof of this assumption as they intend to show the progress of French colonialism and the perceived superiority of Western civilisation. This does not come as a surprise: their author-compiler Georges Norès had been a colonial administrator with many years experience. In short, these booklets tried to present the achievements of European suzerainty in Indochina to wealthy – and almost exclusively – European audiences who were able to afford an expensive trip to and within Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia (Bui 2021: 49).

Bibliography:

Bui Thi He (2021): Tourism and Colonization: Establishment of French Indochina Tourism in the Early 20th Century. MA thesis, Ritsumeikan Asia Pacific University.

Clémentin-Ojha, Catherine and Pierre-Yves Manguin (2007): A Century in Asia: The History of the École Franҫaise d’Extrême-Orient 1898–2006. Singapore: Editions Didier Millet.

Dauthendey, Max (1924): Letzte Reise: Aus Tagebüchern, Briefen und Aufzeichnungen. München: Langen.

Demay, Aline (2014): Tourism and Colonization in Indochina (1898–1939). Newcastle-upon-Tyne: Cambridge Scholars’ Publishing.

École navale (2022) <http://ecole.nav.traditions.free.fr/officiers_nores_georges.htm> [accessed on 24 July 2023].

Les entreprises coloniales françaises (2014): Pluie rouge: titulaires de la Légion d’Honneur ayant exercé une activité civile en Indochine. <https://www.entreprises-coloniales.fr/inde-indochine/Legion_honneur_1886-1944-IC.pdf> [accessed on 24 July 2023].

Hesse, Hermann (1980): Aus Indien: Aufzeichnungen, Tagebücher, Gedichte, Betrachtungen und Erzählungen. Frankfurt: Suhrkamp.

Kinloch, Charles Walter (1853): De Zieke Reiziger; or Rambles in Java and the Straits in 1852 by a Bengal Civilian. London: Simpkin, Marshall & Co.

Norès, Georges (1930): Itinéraires automobiles en Indochine: guide du touriste. Volume 3: Annam, Laos. Hanoi: Imprimerie d’Extrême-Orient.

Ponsavady, Stéphanie (2018): Cultural and Literary Representations of the Automobile in French Indochina: a Colonial Roadshow. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

[1] For a more detailed account of this collection there will be an article in the forthcoming issue of the Newsletter of the South East Asia Library Group.

[2] Actually, German author Max Dauthendey passed away from Malaria in 1918 in a hill sanatorium in the Malang region in East Java (Dauthendey 1924).

[3] For biographical information on Georges Norès see École navale (2022) and Les entreprises coloniales françaises (2014).

[4] On the role of EFEO as colonial institution see Clémentin-Ohja & Manguin (2007: 33–38).

[5] EFEO already had their own printing press in Indochina in 1901 (Clémentin-Ohja & Manguin 2007: 212).

Recent Comments